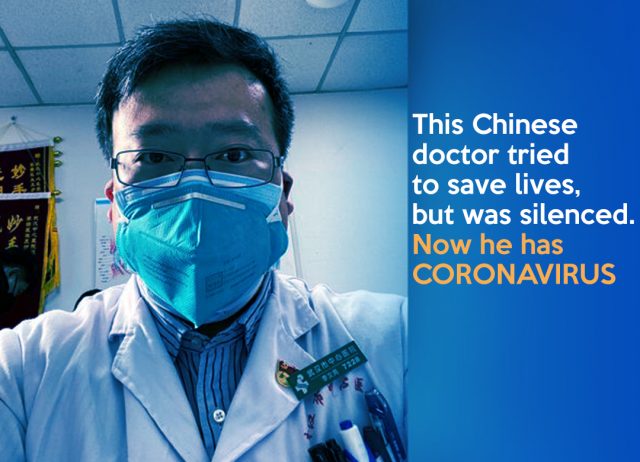

On Dec 30, 2019, Li Wenliang, a doctor by profession who was working as a doctor in Wuhan created a hoax in his medical school alumni group on the popular Chinese messaging app WeChat as he informed the group members about the diagnosis of SARS-like illness in seven patients, being quarantined in his the hospital he served, that came from a local seafood market.

Li suggested that they tested positive for a test and the illness was likely to be a coronavirus – a large family of viruses that results in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Reminiscent of 2003 nationwide outbreak of SARS that killed hundreds in the country following a cover state-sponsored government, the SARS is now a problem not only for mainland China but also the global society. “I only wanted to remind my university classmates to be careful,” Li, 34 said.

The poor doctor warned his friends and family in private chats but within next few hours the screengrabs of the chats went viral (without his identity being blurred). “When I saw them circulating online, I realized that it was out of my control and I would probably be punished,” Li said.

Rightly estimated by Li as soon after he made the messages, he was nabbed by Wuhan police for spreading rumor. Li was one of the several medics detained temporarily by police for propagating falsified information to disrupt public order as they attempted to blow the whistle on a potential outbreak that could prove deadly. The virus has since consumed over 560 lives and sickened above 20,000 people across globe.

Li is currently under intensive care after testing positive for virus on last Saturday. The news (diagnosis of the doctor) has sparked a wave of anger across China where nothing escapes from the state control and scrutiny. Chinese authorities unable to warn public in or on time are not only facing backlash from general public but have also been criticized by the Supreme Court.

On the very same day the Li dropped the SARS bombshell in a group on the popular chatting app, an emergency notice was issued by Wuhan Municipal Health Commission to update the city’s medical institutions about an unknown pneumonia suffered by some people that visited Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.

The notice came with a warning: “Any organizations or individuals are not allowed to release treatment information to the public without authorization.”

Wuhan’s health authorities in the early hours of Dec 31, 2019 meet up in an emergency meeting to discuss the spread of the strange disease. Afterwards, Li was called up by officials at his hospital to give an explanation about the cases he speculated about, according to the reports of newspaper Beijing Youth Daily.

Later that day, Wuhan authorities made admission of the outbreak to the public and alerted World Health Organization. But Li’s still had to cough up. Li with the arrival of the new year, on Jan 3, 2020 earned an unpleasant surprise when he was summoned at local police station and was scolded for spreading false information online and severely disrupting social order with the message, he made in the chat group.

Li signed an apology and acknowledged his misdemeanor while promising not to commit further breaches of law set by the state authorities. He feared of being detained. “My family would worry sick about me, if I lose my freedom for a few days,” he contacted CNN over a text message on WeChat as he couldn’t speak because of the uncontrollable coughing and poor breathing.

The ophthalmologist was allowed to leave the police station after an hour after facing some music for his wrong work. He said: “There was nothing I could do. (Everything) has to adhere to the official line.”

On Jan 10, 2020 while treating a patient infected with the coronavirus at his hospital, the doctor started t cough and was hit with fever the next day. On Jan 12, 2020, he was hospitalized before being admitted to the intensive care and given oxygen support. Li was diagnosed with coronavirus on Feb 1, 2020.

Chinese authorities playing down on the pandemic like in the past, enforced all the measures to hush the public for speaking to anyone or sharing anything about the outbreak. On Jan 1, police announced that they have taken legal actions against 8 people involved in polishing and sharing rumors online.

“The internet is not a land beyond the law … Any unlawful acts of fabricating, spreading rumors and disturbing the social order will be punished by police according to the law, with zero tolerance,” said a police statement on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like platform. The statement surfaced across mainstream media and state-broadcaster CCTV, to let public know that Chinese authorities will not tolerate any thing that differed form their narrative.

As the uproar started to begin after Beijing Youth Daily conducted an interview of Li that quickly spread online and excerpts of it went viral online. Chinese Supreme Court on Jan 28, criticized the Wuhan police for going against the rumormongers.

“It might have been a fortunate thing for containing the new coronavirus, if the public had listened to this ‘rumor’ at the time, and adopted measures such as wearing masks, strict disinfection and avoiding going to the wildlife market,” the Supreme Court commentary said.